A Gruesome Reckoning: Librarian Sifts Mexican Press to Tally Drug-Cartel-Related Killings in Juárez

Ana Campoy, Wall Street Journal (June 15, 2010)

With 2,633 homicides in 2009, murder in Juarez, Mexico, is out of control. Much of the violence is related to drug trafficking, accounting for gang on gang and police killings. But civilians are attacked, too, in displays of intimidation, or are simply caught in the crossfire or randomly targeted, like the pregnant U.S. consulate worker and her husband last March. To get a sense of the violence and corruption, listen to this chilling interview with Charles Bowden, a journalist who has covered Juarez for fifteen years and author of Murder City: Ciudad Juarez and the Global Economy’s New Killing Fields .

.

Due to the complexity of determining when a murder, especially a seemingly random one, is related to the drug cartel — compounded by national outrage and international scrutiny that may encourage Mexican authorities to obfuscate the facts — there are no official counts of drug-related murder. This has led researchers, media organizations, watchdog groups and others to keep their own tallies, but this quickly becomes overwhelming because the killings are happening constantly.

Enter librarian Molly Molloy of New Mexico State University. She runs the Frontera List, a collection of newspaper articles about issues along the U.S.–Mexico border. More importantly, she tracks the Mexican media for reports of drug-trade-related murder, keeps them in a searchable database and provides free daily updates and analysis to researchers, journalists, members of Congress, human-rights observers, and more.

While Molloy’s findings contribute to current U.S. news reports, academic studies and investigative journalism, including Charles Bowden’s book Murder City, she also hopes to develop an archive at her university’s library for future scholars that will be useful for analyzing trends over time. Her work has also been essential in unexpected ways, such as providing evidence of fear and distress for a refugee seeking U.S. asylum.

From the Wall Street Journal article:

Ms. Molloy said her work also could help the refugees. Earlier this year, a lawyer representing a person seeking U.S. residency asked Ms. Molloy for documentation of a body—and a severed head—deposited near the client’s home. Ms. Molloy found an article on the incident by searching her database for “decapitated.”

The client’s visa was approved.

As a librarian, I’m naturally heartened and enthused by the idea of a concerned librarian–researcher mending a crucial information gap. But this situation has other fascinating information facets, namely, the authority to name and classify.

What constitutes death is transparent, and murder, close to it. But less evident is defining what is and is not related to drug trafficking, as well as attaching meaning to what this entails (as a significant market for Mexican drugs, is not the United States complicit?). The power seems to be shifting hands: from the Mexican government and police to journalists on the ground to a diligent librarian in New Mexico observing, dissecting and freeing information.

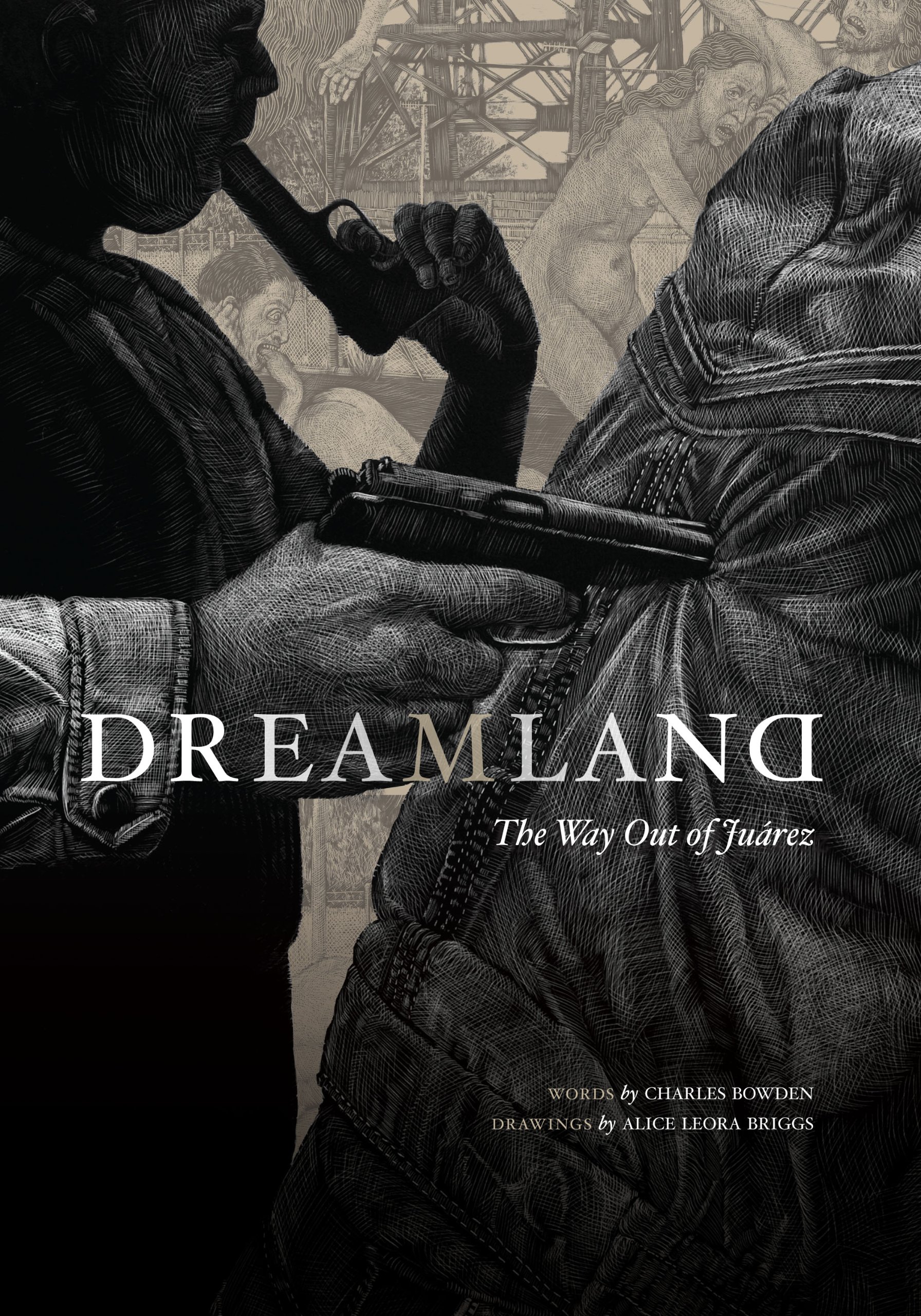

, a mix of journalism and evocative, literary expression with haunting illustrations by Alice Leora Briggs.