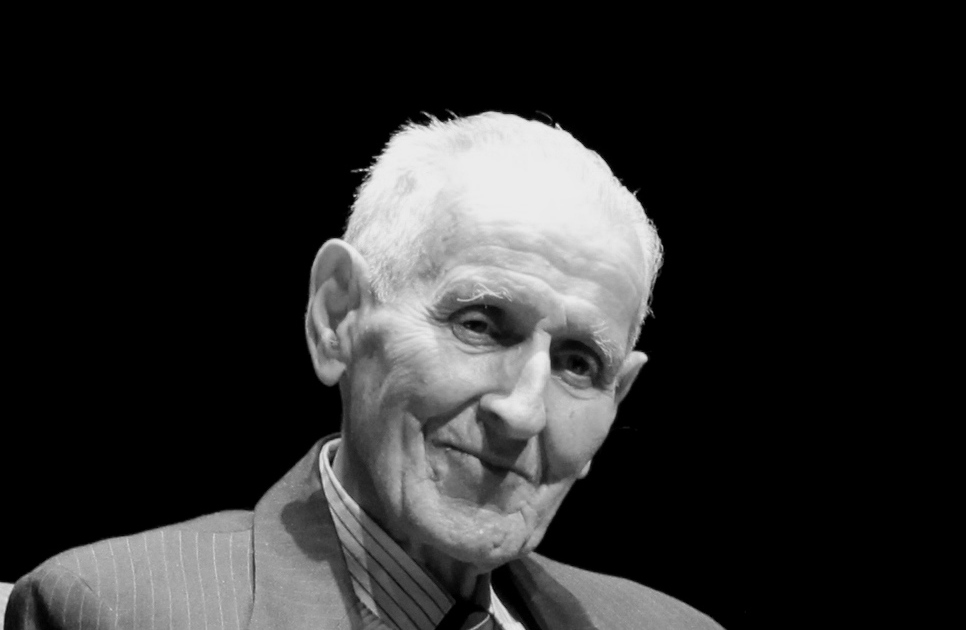

My good friend Juanita Garciagodoy died on Thursday, October 27, 2011. She was 59.

In July 2009, Juanita told me via e-mail that she had breast cancer and that it had metastasized. This was at the same time that the Death Reference Desk launched. I had sent Juanita a rather silly message about why she should check out the Death Reference Desk since she was a Meso-American studies scholar who had written about the Day of Dead (Día de los Muertos). She responded with her usual strong support and the fact that she was dying.

Suffice it to say that I felt like an idiot. A big one.

I promised Juanita that after she died, I would write about her for the Death Reference Desk. She reminded me of this promise over the years, most recently in our very last e-mail communication at the end of September 2011:

John,

Thank you for your sweet note.

Remember? You owe me an obituary, my friend. No pressure, of course.

Love,

Juanita

Que Si, Juanita Garciagodoy. I do remember. And with tears streaming from my eyes while I type these words, I am honored to remember our friendship in writing.

Que Si, Juanita Garciagodoy. I do remember. And with tears streaming from my eyes while I type these words, I am honored to remember our friendship in writing.

I first met Juanita in October 2001 at an academic conference in Puebla, Mexico. It was the first time that I presented my Ph.D. research on the dead body and Juanita was unbelievably enthusiastic about my studies. Without any question, Juanita was the first academic from outside my own institution who expressed deep interest and support for my work. That we met in Mexico was a little ironic since she was a Professor at Macalester College in St. Paul, Minnesota and I was at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis, Minnesota.

Juanita and I stayed in touch over the years, mostly by e-mail. From time to time she would send me news articles about a dead body topic. And by send, I mean she would physically cut them out and put the articles in the mail. I was particularly fond of the article on beetles that strip away cadaveric flesh. In 2005 she attended my Ph.D. defense (which is true sign of selfless friendship, let me just say) and in 2006 she brought an entire crowd of people to watch my one-man show On The Untimely Death of John Erik Troyer, Ph.D. at the Bryant-Lake Bowl Theatre. In a nutshell, Juanita showed herself to be a wonderful friend during important moments in my adult life.

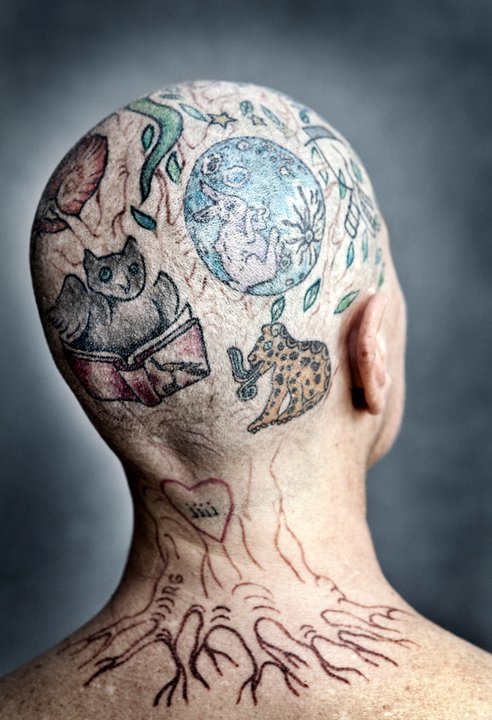

In June 2010, I gave a keynote lecture on Memorial Tattoos for the Death, Commemoration, and Memory conference in Edinburgh, Scotland. Over the last few years, I’ve begun researching the history of tattooing and its relationship to human mortality. A central figure in that talk was Juanita. Indeed, Juanita has become (and will remain) a key figure in any talk that I give on tattooing.

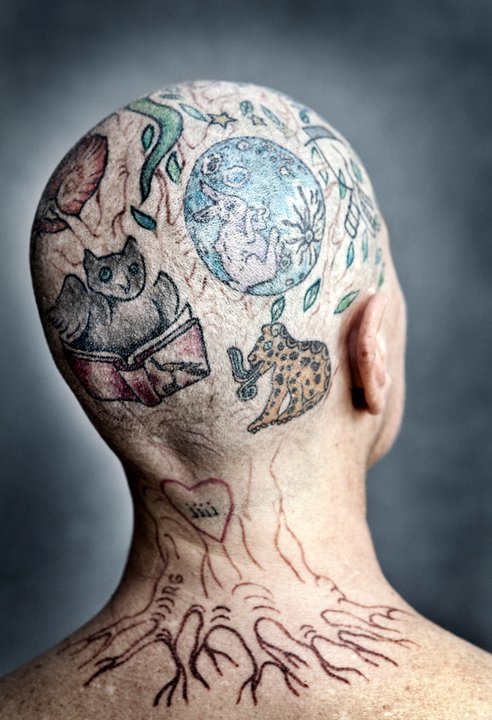

After Juanita lost her hair due to radiation treatments, she decided to cover her head with tattoos. It is important to note, I think, that prior to this moment Juanita had never gotten a tattoo of any kind before. So not only did she choose to get a tattoo, she chose to tattoo her head – the most visible (and next to the face) hardest part of the tattooed human body to hide. Over a course of months, Juanita went from zero tattoos to a head full of colorful ink. She had her tattoos done at Leviticus Tattoos in Minneapolis, which I know she would want people to know.

It is Juanita’s tattoos that I want to discuss and remember the most. To the end of her days she defied conventional wisdom about how a person should live her life while dying from breast cancer. Her tattoos were, for me, a brilliant and moving outward expression of that defiance.

Juanita also had some seriously bad ass ink and the stories that her tattoos tell/told bear retelling here.

When Juanita first lost her hair she experimented with painting her head, but the paint rubbed off so she decided that tattoos were the logical solution. She and I spoke at length about the deeper reasons for the tattoos; the reasons that turned her tattoos into a profound choice about confronting death.

She saw the tattoos as part of her identity and she felt that the visual collage on her head helped her assert the inevitability of her own death. On more than one occasion, Juanita told me that her tattoos were both a confrontation with life and a liberatory act in the face of death.

She saw the tattoos as part of her identity and she felt that the visual collage on her head helped her assert the inevitability of her own death. On more than one occasion, Juanita told me that her tattoos were both a confrontation with life and a liberatory act in the face of death.

A great irony attached itself to her tattoos: Juanita wanted the tattoos so that people would talk about something, anything, other than her cancer. I always admired this particular reason – instead of waiting for the other person to think of a conversation topic, just give that person a bunch of tattoos staring them in the face as a tour de force kind of ice breaker. Sadly, and on many occasions, people would go to great lengths to avoid discussing the tattoos. She and I laughed about this situation, since her tattooed head was an obvious discussion topic. Alas, many people were either afraid to ask or couldn’t be bothered and it was their loss.

Here, then, are the stories that Juanita’s tattoos tell (as told to me by Juanita) and in no particular order:

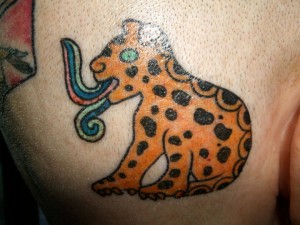

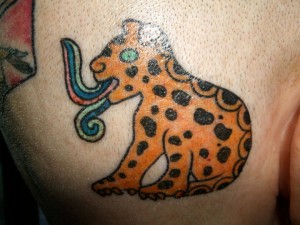

The Singing Jaguar: a Meso-American poet symbol. Juanita wanted a representation of an ancient poet symbol to reflect her own writing.

Ozomahtli the Monkey: Mexican seal used to imprint objects. Juanita always felt that it was a beautiful design. Ozomahtli is also associated with spring, with song, with poetry, and with fertility in other contexts.

Ozomahtli the Monkey: Mexican seal used to imprint objects. Juanita always felt that it was a beautiful design. Ozomahtli is also associated with spring, with song, with poetry, and with fertility in other contexts.

Grasshopper on Mountain: Pre-Spanish design from an Aztec art book. This was also the symbol for Juanita’s favorite park in Mexico City.

Rabbit in the Moon: In Meso-American story telling, Rabbit is said to have previously been a god, a humble god, who agreed to illuminate the night. As a result, Meso-American storytellers described seeing a rabbit in the moon. The rabbit was designed by friend from a prehistoric pot image. The moon image is taken from NASA, complete with craters. Juanita told me that she felt close to the moon. For her the moon was poetic and mysterious.

Owl hovering over a Book: The owl represented wisdom and it showed Juanita’s commitment to knowledge by reading the book. The peacock on the book’s cover is taken from the cover of a novel by her husband George. Juanita also explained to me that there is an old Mexican saying: When the owl sings the Indian dies. She believed that this saying described a confrontation with mortality that she, herself, was going through.

Owl hovering over a Book: The owl represented wisdom and it showed Juanita’s commitment to knowledge by reading the book. The peacock on the book’s cover is taken from the cover of a novel by her husband George. Juanita also explained to me that there is an old Mexican saying: When the owl sings the Indian dies. She believed that this saying described a confrontation with mortality that she, herself, was going through.

Cheshire Cat: Juanita wanted a cat tattoo and she loved Alice in Wonderland. This was also a tattoo to remember all the dead pets.

Cheshire Cat: Juanita wanted a cat tattoo and she loved Alice in Wonderland. This was also a tattoo to remember all the dead pets.

Heart with jjjj: This was a code for “Juanita’s Handsome Husband Jorge.” I can’t replicate the accent that Juanita used to say those words, but it was very funny. The heart was also for love since Juanita and George loved each other very deeply.

Tree: The tree of knowledge which surrounded her head.

Snake: A symbol of knowledge and transgression, as when Eve eats the apple in the Garden of Eden.

Snake: A symbol of knowledge and transgression, as when Eve eats the apple in the Garden of Eden.

Humming Bird sipping out of a Star: Juanita loved the beauty of this image. The Hummingbird is also featured in ancient Meso-American stories. Three groups of people turned into hummingbirds or butterflies when they died: warriors who died in battle, people who were sacrificed, and women who died in childbirth. Juanita told me that at times she felt like her own body was sacrificing itself and betraying her. She often felt that she was battling cancer as a warrior.

El Don Quixote: Last but not least. Don Quixote was her first tattoo. Initially, Juanita was only going to get Don Quixote because she was told that the process might hurt. As is totally obvious, Juanita had the exact opposite reaction to the pain from that first tattoo. The image is by the artist Posada. Juanita told me that Posada was the kind of artist who pulled death into life with a great sense of humor. El Don Quixote also reminded her of the Day of the Dead, which was an area of her own research. Her 2000 book, Digging the Days of the Dead: A Reading of Mexico’s Dias de Muertos, had three Don Quixote’s on its cover.

One other important detail: all of the creatures have green-blue eyes, like Juanita’s eyes.

Even after it was possible for Juanita to grow her hair back, she decided to keep her head shaved. It was important to her that the tattoos be visible. Juanita explained to me that her tattoos were producing stories about her and her life.

Those tattooed stories, which live on today and will thrive for some time to come, are the narrative traces of Juanita Garciagodoy’s life.

These stories are also Juanita’s permanently inked memorial.

Que Si, Juanita Garciagodoy. I do remember. And with tears streaming from my eyes while I type these words, I am honored to remember our friendship in writing.

Que Si, Juanita Garciagodoy. I do remember. And with tears streaming from my eyes while I type these words, I am honored to remember our friendship in writing.

Snake: A symbol of knowledge and transgression, as when Eve eats the apple in the Garden of Eden.

Snake: A symbol of knowledge and transgression, as when Eve eats the apple in the Garden of Eden.